Because the ‘Oxalis season’ has begun in earnest (Oxalis pes-caprae, which grows fall-spring in our mediterranean climate), I thought an article about what I know would be timely. My research, which I usually perform before such an article, brought up far more than I had anticipated! Because this South African Oxalis species has gradually become more widespread in California as well as other places in the world, it has attracted more attention from professional botanists, gardeners, as well as laymen who enjoy the ‘natural’ world.

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, ‘sourgrass’ was part of my childhood. The stems of O. pes-caprae delighted me and other children in their decidedly sour taste (oxalic acid) and we used to much on them when found growing in agricultural fields (which surrounded us) or in local gardens. They were present but not particularly weedy at that time (the 1950-60s).

As I entered adulthood, I started to notice this species appear in areas where it had not been before. Over time, those small patches of O. pes-caprae became larger. Abandoned gardens which had only a corner of ‘sourgrass”’ became full infestations a number of years later. In my gardening pursuits, I was grateful that I seldom had to deal directly with this invader, that is, until I started to consult with homeowners throughout our area – one of the common reason I was called in was that this introduced plant was overwhelming their gardens.

While researching effective ways to combat these infestations, I learned that O. pes-caprae had become a serious problem in various other parts of the world besides California!

Most of the papers and articles I was able to find dealt with the possible ways in which O. pes-caprae was introduced and how it was spreading into new areas. Rather than accidentally ‘hitching a ride’ as many of our weeds have when humans moved around the planet, this plant seems to have been intentionally brought to new places as an ornamental plant. In fact today, I am able to find more than one source offering it for sale, extolling its beauty and ease of growing!! (buyer beware)

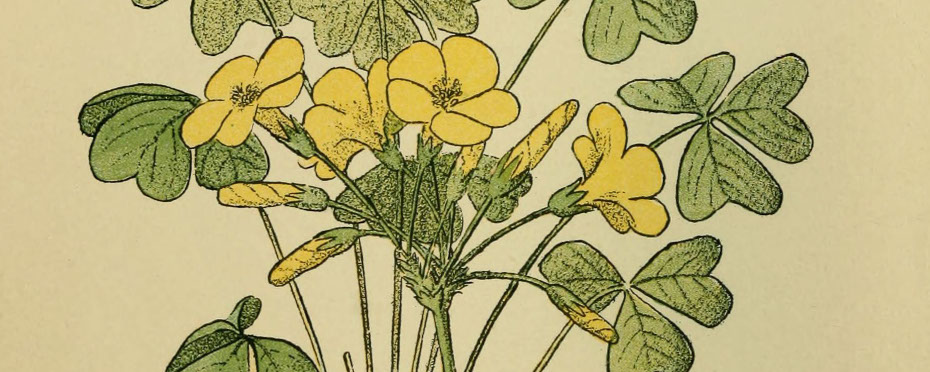

Often when people complain about this pest on today’s social media, you can find other commenting “but it’s so pretty!”. For those, I suggest purchasing one of the many fine photographs, watercolors, or paintings of O. pes-caprae flowers that are also being offered on the Internet.

In the past, knowing that this species grows from underground bulbils after a summer dormancy seemed to be most of what was known. These are small bulb-like structures, produced in an axil (where a leaf attaches to a stem), on a flowering shoot, or on the roots. Many different plants produce types bulbils which can form a new plant that is a clone, or exact replica, of the original. Several Oxalis species produce bulbils, either below or above ground, or both. The dormancy of these species may in winter or summer, depending on where they originate. In this article, I am addressing only what I have observed from Oxalis pes-caprae.

Many assumptions seem to be made about the bulbils of O. pes-caprae – that they are persistent and that they multiply like true bulbs. It turns out, they behave very differently than those and even from the bulbils of some other Oxalis species.

A Brief Botanical Break

Oxalis pes-caprae L., Sp. Pl.: 434 (1753)

ah-ZAW-lis pes-CAP-rye (pronunciation info)

Synonyms

Acetosella cernua (Thunb.) Kuntze, Revis. Gen. Pl. 1: 90 (1891)

Acetosella sericea (L. fil.) Kuntze, Revis. Gen. Pl. 1: 91 (1891)

Bolboxalis cernua (Thunb.) Small, Britton & Underw. (eds.), N. Amer. Fl. 35: 28 (1907)

Oxalis burmanni Jacq., Oxalis 41 (1794)

Oxalis cernua Thunb., Oxalis 6, 14-16, tab. 2 (1781)

Oxalis cernua var. pleniflora Lowe, Man. Fl. Madeira 1(1): 100-101 (1857)

Oxalis libica Viv., Fl. Libyc. Spec. 24-25, tab. 13 fig. 1 (1824)

Oxalis pes-caprae f. pleniflora (Lowe) Sunding, Cuad. Bot. Canar. 13: 17 (1971)

Oxalis pes-caprae var. sericea (L. fil.) T.M. Salter, J. S. African Bot., Suppl. 1: 76 (1944)

Oxalis sericea var. pilosa Ball, J. Linn. Soc., Bot. 16(94): 388-389 (1878)

Oxalis sericea L. fil., Suppl. Pl. 243 (1782)

… (see even more synonyms!)

Etymology

There are various similar versions of what Oxalis means, but generally it is from the Greek οξος (oxos), vinegar/sour ; The species pes-caprae: is from the Latin pes, or foot, and the Latin caprae, or goat – ‘goat-foot’, referring to the leaflet shape.

Common names

Bermuda buttercup, Bermuda clover, buttercup oxalis, Cape sorrel, goat’s foot, soursop, sourgrass, yellow oxalis,

Like some other Oxalis species, O. pes-caprae has curious ‘tristylic’ flowers of different types, presumably as a means of promoting cross-pollination. Individuals of each type exist in a natural population (clonal populations tend to be of the same type).

This species survives the summer dry period in which it evolved by means of bulbils it forms toward the end of its growth cycle, having exhausted the bulbil from which it grew in response to rainfall in autumn. It also has a unusual, tuber-like ‘contractile root’ (shown a left bottom in the next photo) that can pull the bulbil deeper into the soil or away from other competing plants. This ‘contractile root’ lasts only for the growing season leaving just the newly created bulbils.

In its native ranges in South Africa, populations of O. pes-caprae are highly variable. Typical diploid (2x – pairs of chromosomes) are common, but so are individuals that are tetraploid (4x) and even hexaploid (6x). A mostly sterile pentyploid (5x) also exists. Diploid (2x), tetraploid (4x), and hexaploid (6x) are fertile and can produce seeds, but all forms can and do produce clonal bulbils, with the higher ‘ploidy’ producing a larger number each season!

Where I live in California, the sterile pentyploid (5x) variant seems to be the main type that has been introduced, which is why it is nearly impossible to find seed pods on our plants. From what I have read, other countries often have a mix of forms, likely the result of how the plant made its way to those regions.

In the References and Links section below, I have included a large number of links to various botanical papers and studies. Because of the impact this one species has had on our world, many botanists and environmentalists are studying it carefully and our understanding is increasing.

The lifecycle of O. pes-caprae (and the gardener)

Summer #1 : A number of dormant bulbils are lying in the dry summer soil.

Fall/Winter : In response to fall rainfall, the O. pes-caprae bulbil awakens. A given brown bulbil may contain one or more actual bulbil that sends forth a shoot and root. As these plants grow, the original bulbil is is exhausted completely (this fact is very important!).

A clump of small leaves appears on top of the soil – these are tightly packed together making a sort of ‘knot’ above the ground surface. While the weather is now wetter, the temperatures are dropping and this clump slowly increases.

Winter : During any break in the cold weather, this clump may start to increase, adding more and more leaves. At this point, it is easy for the gardener to ignore them, promising to get to them in due time! And, besides, they make a nice green carpet where the soil was once bare.

Spring : All of the sudden, the season has apparently progressed rapidly and the gardener is now reminded that there are O. pes-caprae lurking here and there by their bright yellow flowers!! The improving weather also inspires a desire to work in the garden, so, finally pulling the Oxalis is on the agenda.

But the problem is that, at this point, O. pes-caprae has already produced new bulbils in the soil and likely above ground bulbils at the base of the plant as well. Trying to remove all of these while pulling up the flowering plants is an exercise in futility!!

Summer #2 : More new bulbils are now lying dormant on top of and in the dry summer soil. Argh!!

During their summer dormancy, these bulbils, whose outer covering dries to a soil-brown color, can unsuspectingly be moved around your garden as part of garden maintenance or renovation. And, if you have soil removed, they can travel to another garden (“Free soil, you haul!”) or to waste places haulers might discard the load you paid them to take to the dump!

And our local birds have come to know about this food source (or maybe they just think they are acorns?), spreading them around as they try to consume them on a nearby tree limb or rock perch, or burying them in the soil to consume later. Gophers also have learned like them, hording them in their underground burrows!! So before the gardener has gotten around to dealing with the Oxalis, it may already have traveled into new places!

But Wait! There is Still Hope!

If you recall the ‘Fall/Winter’ text above, you will realize that this is the period where there is the least possibility of a bulbil left behind to regrow a new plant later! The idea is to prevent the plant from creating new bulbils, so even it the plant seems to grow right back (and you pull it again), it seems to interrupt the bulbil creation cycle enough.

Your results may vary from year to year, but clients and friends who I have taught this technique, and who have practiced it consistently over a few years, have noticed a significant decrease in Oxalis over time. One client even asked permission to pull plants from a neighbor’s neglected garden adjacent to hers in order to prevent reintroduction!! (they are both Oxalis-free today)

Hand pulling is tedious, especially in the colder, wetter time of the year, but not hard. In our current year, just after New Year’s Day is a good time, but it might be earlier or later depending on rainfall. With your fingers, find the root just under the ‘knot’ of leaf bases, then pull. Inspect the long root it to see if bulbils have already formed, in order to gauge of your timing.

How you dispose of your hand-pulled Oxalis is important – the succulence of this species keeps it from wilting right away like some weeds. Leaving it in a pile in the garden might help it produce new bulbils (as its last gasp!) before you finally dispose of it. Your home compost bin certainly would not get hot enough to prevent the possibility of bulbils surviving. If your community has a large scale green waste composting program, it is likely fine to send it into that process. If you live somewhere without such a program, or if you are uncertain, special disposal such as microwaving or soaking in a vinegar solution for a few days can be effective.

While hand pulling is possible with spot infestations in a garden, large scale field infestations would be best addressed by repeated mowing or even cultivating during this same time period. Spraying is often recommended, but results are limited and it poisons the environment. I’ve even tried using a flame weeder, but O. pes-caprae is so very succulent that its like steaming vegetables (takes a while) and seldom kills the plant. Solarization (covering the soil with sheets of plastic) seems to also have limited success in that the dormant bulbils can been too deep to be effected.

Planting a very dense groundcover at least 2ft tall can be effective is shading out an infestation, but usually gardeners wish to have more choice in their plantings!

References and Links

(*Information retrieval date for the URL mentioned)

A natural history of that little yellow flower that’s everywhere right now

https://envirocentersoco.org/updates/2015/03/a-natural-history-of-that-little-yellow-flower-thats-everywhere-right-now/ (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae.

https://www.pacificbulbsociety.org/pbswiki/index.php/Oxalis_pes-caprae (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae. Bermuda Buttercup.

https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=35642 (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae L. Bermuda buttercup, Sourgrass

https://www.calflora.org/app/taxon?crn=6016 (*January 2024)

History vs. legend: Retracing invasion and spread of Oxalis pes-caprae L. in Europe and the Mediterranean area

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0190237

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/figures?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0190237 (*January 2024)

Global Invasive Species Database. Oxalis pes-caprae.

https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=1599 (*January 2024)

The worldwide invasion history of Oxalis pes-caprae revealed by genotyping by sequencing.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358742336_The_worldwide_invasion_history_of_Oxalis_pes_caprae_revealed_by_genotyping_by_sequencing (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae L.

https://flora.org.il/en/plants/oxapes/

Invasion genetics of the Bermuda buttercup (Oxalis pes-caprae): complex intercontinental patterns of genetic diversity, polyploidy and heterostyly characterize both native and introduced populations.

https://europepmc.org/article/med/25604701 (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae f. pleniflora (Lowe) Sunding (Oxalidaceae), A New Record for the Flora of Turkey

https://www.idosi.org/aejaes/jaes7(5)/17.pdf (*January 2024)

Oxalis pes-caprae L., Buttercup oxalis (Bermuda buttercup)

https://wric.ucdavis.edu/information/crop/natural%20areas/wr_O/Oxalis.pdf (*January 2024)

Asexual populations of the invasive weed Oxalis pes–caprae are genetically variable

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0135 (*January 2024)

Distribution of Flower Morphs, Ploidy Level and Sexual Reproduction of the Invasive Weed Oxalis pes-caprae in the Western Area of the Mediterranean Region

https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/99/3/507/2464795 (*January 2024)

The Biology of Australian Weeds. 31. Oxalis pes-caprae L.

https://caws.org.nz/PPQ1112/PPQ%2012-3%20pp110-119%20Peirce.pdf

How to Manage Pests – Pests in Gardens and Landscapes. Creeping Woodsorrel and Bermuda Buttercup.

https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7444.html (*January 2024)

Five Reasons it’s Okay to Love Oxalis – and Stop Poisoning It

https://sfforest.org/2015/05/11/five-reasons-its-okay-to-love-oxalis-and-stop-poisoning-it/ (*January 2024)

Sourgrass Natural Dye Video Tutorial

https://www.santacruzmuseum.org/tag/natural-dye/ (*January 2024)